The Malta Business Registry has erased the records of over 30,000 companies “struck off” from its online registry system, wiping out any knowledge of those involved in dodgy deals and their connections.

This is highly unusual. Countries normally allow a period of time in which records can be checked, for obvious reasons. In the UK, for example, which is also subject to EU data protection laws, full searches relating to dissolved companies are available online and fully searchable for at least six years after dissolution.

Malta went for instant removal of details after a company is struck off, meaning a company can be set up, do its dirty deeds and disappear within a few months.

In July, Economy Minister Silvio Schembri announced that the Malta Business Registry (MBR) had, in a move apparently aimed at impressing Moneyval, removed around 10,000 dormant companies from the register.

Facebook post by Economy Minister Silvio Schembri about the striking off of 10,000 ‘defunct’ companies.

With this latest development, the MBR did far more than merely strike off companies but literally purged any evidence of old companies and their past activities from the MBR’s online system.

Moreover, the number of companies affected by this purge are far more than those announced, with 30,000 being a conservative estimate.

Anyone looking up liquidated companies could previously consult financial records filed by such companies, including their liquidation accounts, as well as the individuals previously involved.

Following this purge of data, the online system only shows very basic information such as the name of the company, its company number and former date of incorporation.

The MBR still allows physical inspection of company documents, against a €20 per file charge, but this involves physically going to the MBR’s offices in Zejtun and, more importantly, knowing exactly what information is sought.

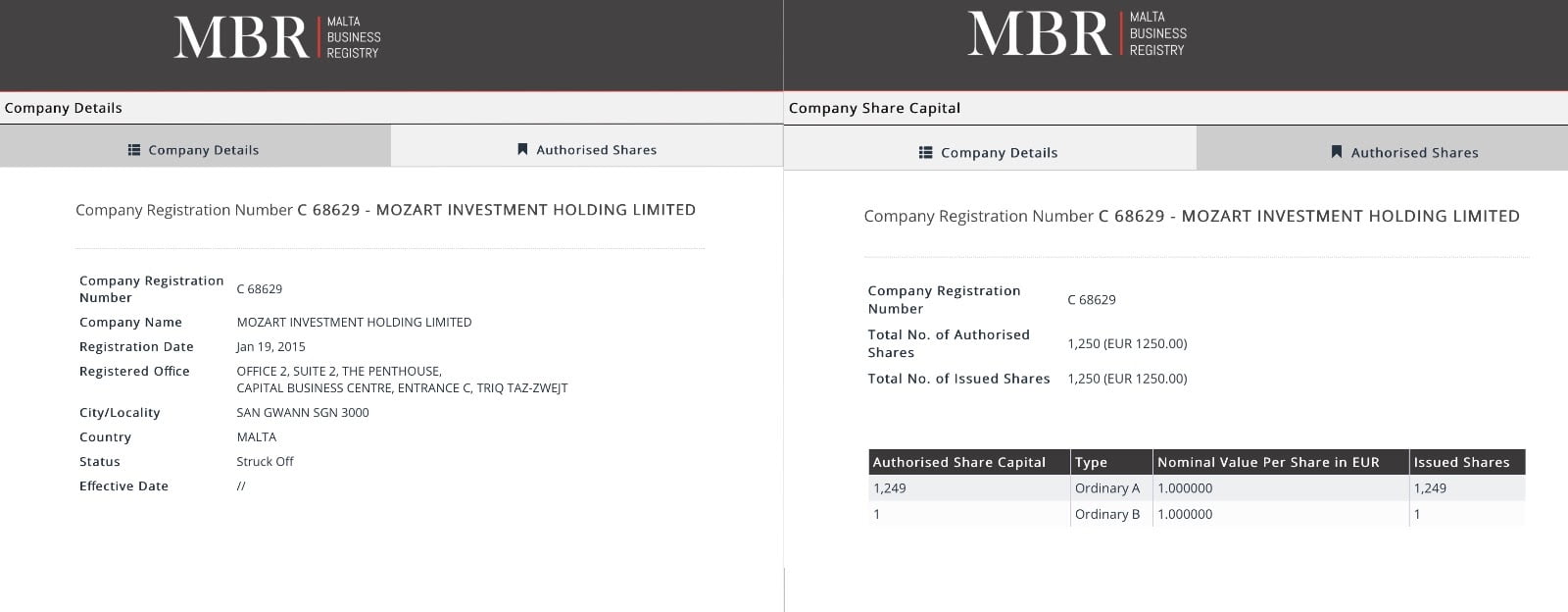

By way of example, in late 2014 Azerbaijani President Aliyev’s close collaborator Manuchehr Ahadpir Khangah set up a series of companies in Malta named after famous composers through Nexia BT’s services. The companies were curiously set up after disgraced former Prime Minister Muscat’s visit to Azerbaijan and then liquidated after just one year. This was discovered by journalists using MBR’s online system.

While users could then see the names of companies’ directors, shareholders, auditors and look at their accounts, this is now all that remains of these companies:

Visual of the very limited information now available on the MBR online system (even for logged in users) in relation to liquidated companies. Source: registry.mbr.mt

This is not the only example of companies that have since been liquidated but which remain a public interest concern.

In 2018, the Maltese government, with Schembri leading the charge, had rebranded Malta as “Blockchain Island”, a move which commentators described as blatant reputation management following the assassination of journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia.

While “Blockchain Island” has since fizzled out, the hype and incentives resulted in a veritable gold rush by Russians, Chinese and others setting up companies in Malta.

Two years later, not a single cryptocurrency operator has been licensed and hundreds have since been liquidated. With this overnight purge, all that remains online is their often nondescript former name.

The MBR’s purge appears to have been indiscriminate, removing details and documents relating to all liquidated companies irrespective of when they were removed from the register.

Practitioners pointed out that shareholders and creditors have certain rights that continue even after a company has been removed from the register. At law, a shareholder or creditor has the right to apply to the Court, for a period of up to five years after striking off, to restore a company to the register.

If the public is deprived of the right of easy access to information this makes exercising their rights, or even knowing that they may need redress, much harder.

Lawyers consulted by The Shift pointed out that, although EU data protection laws include concepts such as deletion of old personal data or data minimisation, it is not clear on what basis the MBR proceeded to indiscriminately purge a public register.

The MBR’s register is mandated by law and required to be kept open to inspection by the public, so many of the requirements of data protection laws do not even apply to the public register, they pointed out.

They also noted that much of the information removed by the MBR does not even relate to individuals but to companies – such as certificates of incorporation or financial accounts.

Accordingly much of that information is not even intended to be covered by data protection laws which, by design, only applies to people.

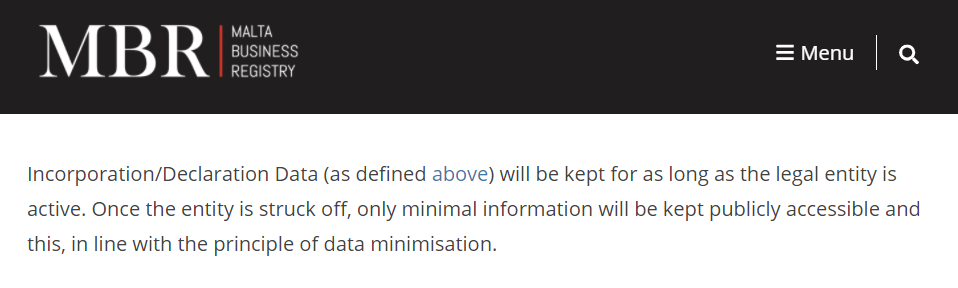

This contradicts statements by MBR that data is being purged “in line with the principle of data minimisation”.

Excerpt from MBR’s privacy policy. Source: mbr.mt

Queried about the reference to “data minimisation” cited by the MBR in their privacy policy, data protection lawyers noted that this concept may have been wrongly applied.

They noted that data protection principles including data minimisation (the requirement to not process excessive personal data) are “not a one way street”.

The MBR is still required to process “adequate” amounts of personal data given the purpose of informing the public through a public register.

Lawyers also pointed out that data minimisation is not a new requirement. It has been a requirement in the EU since 1995 (2001 in Malta), so it is unclear what might have motivated this recent dramatic change in approach by MBR.

Data protection laws should not be used as a carte blanche for public authorities to restrict the public’s right to information or, worse, to indiscriminately purge data – least of all from public registers, they stressed.

This is not the first time MBR’s online system’s functionality has been severely restricted. Until a few months ago it was possible to search for directors’ involvements (not shareholders) in Maltese companies but this functionality was also removed overnight by MBR, reportedly citing “data protection” reasons.

The MBR was detached from the Malta Financial Services Authority, the financial regulator, in 2019 in a move which coincided with the agency’s costly relocation to a former bathroom showroom in Triq il-Labour in Zejtun. The Economy Minister’s wife, Deadra, is the second most senior legal officer there.

Questions sent to MBR to address concerns remained unanswered.